In South Africa, the nineteenth century ended with the largest conflict the region had ever known: the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 to 1902, in which the British Empire fought the independent Boer republics for control of the Transvaal region, rich with newly discovered gold and diamonds. The pretext of the declaration of war was based on the refusal of the British to concede to an ultimatum delivered by the Boer republics, stating that they should cease building up their military presence in the region. The British, meanwhile, had made demands that the Boer republics grant foreigners residing in their territories (who were mostly British) equal political rights, a demand that had been refused. It was not the first major colonial war fought on South African soil, nor even the first between Britain and the Boer republics, but it was by far the bloodiest. One of the venues we visit on our Alexandra’s Africa Hosted Safaris, near Louis Trichardt in Limpopo Province, is at the heart of where this story plays out.

The story of the Anglo-Boer War is a many-coloured tapestry…

While the official belligerents were Brits and Boers, modern historians often refer to the conflict as the South African War because almost all of the country’s ethnic and cultural groups were inadvertently pulled into this three-year tempest of violence, destruction and suffering. As with all wars, the story of the South African War is a many-coloured tapestry, woven from countless tales of heroism and cowardice, blunders and bravado, sieges and battlefields, defiant last stands and humiliating surrenders, fierce resistance and guerrilla warfare, and the desolation and woe of a scorched earth policy and concentration camps. It is also a story of heroes and villains on both sides, as well as larger-than-life characters, many of whom, like Jan Smuts and Winston Churchill, went on to shape world history in the twentieth century.

Involved in this war were also other characters whose names are not as prominently recorded in the annals of history, but whose exploits were no less fascinating nor impactful. In the international press the conflict was often framed as a David and Goliath one, and it drew adventurers and mercenaries from all over the world, who flocked to both sides’ banners. In many ways it was such a fight; the British Army was the most powerful in the world, made up of professional soldiers with access to the most advanced military technology of the day, while the Boer forces were largely irregular (usually called commando units), made up of farmers and their male family members (all Boer men from the age of sixteen to sixty-five were conscripted), who carried their own hunting rifles and supplies, rode their own horses, and wore neither uniforms nor military insignia.

Officers of the Bushveldt Carbineers in South Africa.

Lieutenants Handcock (far left) and Morant (with dog)

Officers of the Bushveldt Carbineers, including lieutenants Handcock (far left) and Morant (with dog)

Source: https://www.nma.gov.au/

Despite her military prowess, Britain entered the war somewhat unprepared, and made the mistake of underestimating the martial skill, grit and cunning of the Boers, who at the beginning of the war went on the offensive. They invaded the British territories of Natal and the Cape, and besieged a number of British colonial towns in northern Natal (modern-day KwaZulu-Natal). They scored some surprise battlefield victories with their hit-and-run tactics, superior mobility, adaptability to the harsh conditions of the South African bush and superb marksmanship. The British Army however, quickly recovered from this initial misstep and adjusted their approach, and by 1900 the tide of the war had turned significantly.

The third phase… finding men who could ride and shoot…

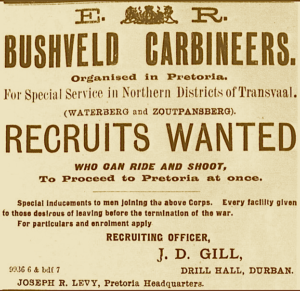

After relieving the besieged towns of Ladysmith and Kimberly in February 1900, and then Mafikeng in May, and the British went on the offensive and took the Boer capital of Pretoria in June. Many Boers realised that the game was up by this time, and that they could not hope to win in open battle against the mightiest military power on earth, and many surrendered at this point. The British formally annexed Transvaal and the Orange Free State and by October 1900 declared the war to be officially over. A large number of dogged Boer fighters, however, refused to give up, and began a devastatingly effective guerrilla campaign against the British – this led to what was known as the third phase of the war, during which Lord Kitchener implemented his ‘scorched earth policy’ and a series of concentration camps mushroomed, and special units of men who could ‘shoot and ride’, known as the Bushveld Carbineers, were sent out to fight what was left of the Boer Commandos on their own turf, with the intention of ending the war.

Source: https://vwma.org.au/explore/units/376

Many of the extra troops Britain brought in as Bushveld Carbineers came from British colonies all across the world, including places like Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Of these territories, the bush of the Australian outback was most geographically and climatically similar to the South African veld in which the guerrilla campaign was being fought, and it was from here that a large number of the men who formed the Bushveld Carbineers (BVC), under the command of the Australian Colonel R. W. Lenehan, were drawn. The BVC was formed with the intention to beat the guerrilla commandos at their own game. The British Army called for volunteers for the unit who could “ride and shoot”; expert horsemen and marksmen who were comfortable living off the land and fighting in an unconventional style of warfare.

Lieutenant Harry “Breaker” Morant

One of these soldiers was Lieutenant Harry “Breaker” Morant. His name is well-known in Australia, and for some Australians his fate is still a sore point in terms of relations between Australia and Britain. Morant, a charismatic horseman who, prior to enlisting in Her Majesty’s Armed Forces in 1899, had spent the better part of fifteen years in small towns in the harsh Australian outback as a drover and horse-breaker – hence the nickname “Breaker”. He achieved minor fame as a bush poet, and some of the excesses of his colourful personality included a penchant for hard liquor and womanising.

When the irregular BVC was formed in February 1901, Morant, then a lieutenant, joined up. Before this, he’d spent his time since arriving in South Africa with the British forces in early 1900 as a dispatch rider.

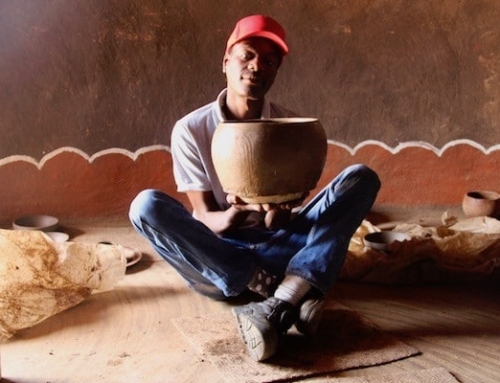

Most soldiers of the BVC were much like Morant; hard men and expert horsemen who had extensive experience in harsh wilderness conditions. Interestingly enough, while many BVC soldiers were Australians, a number of men in the unit were Boers, now fighting against their former comrades. The regiment was stationed at Pietersburg in the Spelonken region of the Northern Transvaal (now called the Hlanganani region of Limpopo Province), which you will have the opportunity to visit on an Alexandra’s Africa tour.

The BVC, whose purpose was to fight the guerrilla Boer units at their own game, saw combat in the area on a number of occasions, but quickly became more well-known for their lawlessness, lack of discipline, womanising, wanton drunkenness and alleged murders. One of the most senior commanding officers was accused of rape and resigned. The incidents that resulted in the court-martial and execution of Breaker Morant and another lieutenant, Peter Handcock, happened in the aftermath of a skirmish in which Captain Hunt of the BVC, a close friend of Morant, was killed and mutilated, and to this day are shrouded in controversy.

1902: British execute horseman, soldier and poet Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant

Harry “Breaker” Morant

Source: https://www.nma.gov.au/

In the subsequent wake of twenty murders of Boer civilians, prisoners of war and unarmed Boers who came in to surrender, an investigation was held and Lieutenants Morant, Handcock and Witton were convicted of the murders. The motive for the murders was allegedly to exact vengeance for the killing and mutilation of Captain Hunt. Breaker Morant and Peter Handcock, who remained defiant until the end, were executed by firing squad, but Witton’s sentence was limited to jail time.

News of the executions immediately stirred up controversy, with claims being made that Morant and Handcock had been scapegoated by the British military leadership, who some people believed had been complicit in the murders. Morant’s supporters believed that he was only following orders, and that those who had given the orders had had him and Handcock killed to cover their tracks. A movie, released in 1980, was made about Breaker Morant’s life, painting him as something of a martyr. There have been numerous petitions made, some as recent as the last few years, to the British government from members of the Australian public, some of whom regard Morant and Handcock as folk heroes, for the pair to be given posthumous pardons.

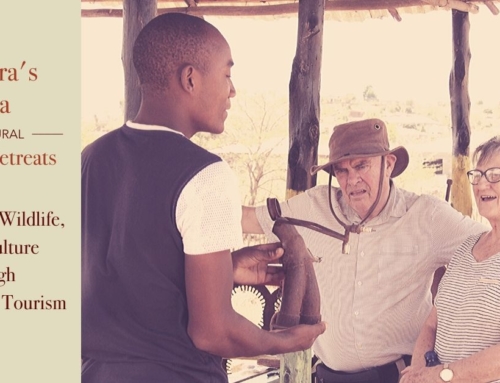

On our hosted Safaris we visit Lalapanzi hotel which is close to Louis Trichardt on the Zoutpansberg Skirmishes route. Inside the hotel there is a little museum with a cornucopia of memorabilia and information dedicated to this controversial regiment – the Bushveld Carbineers.

Alexandra’s Africa is an independent, niche Safari Tour Operator based in the New Forest in Hampshire, UK offering a range of small-group Hosted Safaris, Tailored Safaris and Conservation Experiences. For information or for a chat please contact us on: alexandrasafrica.com/contact or T: +44 (0)2382 354488 or E: alexandra@alexandrasafrica.com.

Sources for this Blog: